With such ambitious and attractive visions, it is easy to see why transect zoning has become the favored model for much of today's urban planning and land use regulation. However, Notre Dame law professor Nicole Stelle Garnett's recent article balances admiration of transect zoning's promises with skepticism of the costs and restrictions associated with these zoning patterns and their closely related form-based codes. Nicole Stelle Garnett, Redeeming Transect Zoning? 79 Brook. L. Rev. (2013). Officially, form-based codes are merely regulatory mechanisms that allow local governments to combat urban sprawl, reverse the deterioration of historic neighborhoods, and support transit-oriented development (all, in this blog's humble opinion, worthy objectives). But these form-based codes are often tied to a particular New Urbanist aesthetic in order to create visible indicators of various transect zones, reverse decades-old troubling development trends, and build consensus among residents of neighborhoods transformed by transect zoning. This imposition of a uniform architectural standard can incur high compliance costs, require the securing of expensive design services and building materials, and raises important policy concerns of legally implementing a particular urban aesthetic. Form-based codes also often include confusing planning jargon that Professor Garnett warns runs the risk of unconstitutional vagueness. See Anderson v. City of Issaquah, 851 P.2d 744 (Wash. Ct. App. 1993). Garnett suggests that municipalities implement mixed-use land environments without attaching the strings of New Urbanist design principles. While this "no strings attached" approach may encounter resistance from some urban planners, the proposed mixed-use land regulations provide a means for cities to achieve the desirable goals of smart growth, historic preservation, walkability, and diverse housing stock without imposing architectural uniformity and prohibitive compliance costs.

|

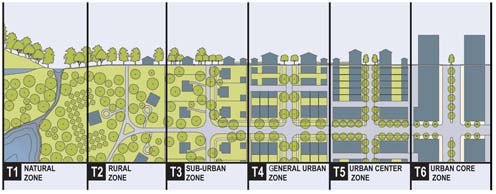

| Image Credit: Center for Applied Transect Studies |

No comments:

Post a Comment